Ritual Gathering Potluck Party

20 August – 3 September 2022

To be launched by Amrita Gill, Artistic Director and CEO – 4A Center for Contemporary Asian Art

Artist in Conversation with Dr. Natalie Seiz, Curator of Asian Art – Art Gallery of New South Wales

Essay by Dr. Shoufay Derz

Photographs by Kathleen Madison

Art Atrium Gallery, 12 Daniel Street, Botany. Australia

https://issuu.com/vania033/docs/jayanto_art_catalogue_18.08.2022_v3_pages

1 packet of egg noodles, garlic, tofu, soy sauce, fish soy, bean sprout (not in the ceramic), chili, shallot, white radish, spring onion, salt and pepper.

- Jayanto Tan

At first glance, it is a seemingly simple list of ingredients that evokes Jayanto’s childhood memories of the special recipe his mother prepared as an offering during Lunar New Year ceremonies and in honour of his late father on Ceng Beng (also known as Tomb Sweeping Day). But as with many seemingly simple encounters, there is often a deeper, richer story waiting to unfold if we give it more attention. After all, it is easy to forget that what is familiar to one person can be completely foreign or inaccessible to another.

A recipe is a kind of secret language in that it contains several stories that are not always mouthed openly but are nevertheless imbibed by our tongues. As a form of language, each plate is a vessel for sensory knowledge that points to something transformative and beyond the spoken word, connecting networks of relationships across the dining table and beyond. As a social exchange, a meal shared can be very intimate, even if the guests do not know or misunderstand each other; it is a connection that does not need to be explained. This is especially true for people with a migrant background, who often face complex multilingual relationships and the gains and losses of transitioning from one language to another. Our taste buds also have to adapt to the new geography. Jayanto spoke three local dialects as a child, as well as Indonesian, before learning Australian English and later the language of visual arts – a language that does not require perfection and which, he notes, is “a way to express your feelings without saying too much”.

Beyond the mere need to survive or stave off hunger, eating together is a possible way of bridging the distance between estranged individuals or between the present and the past. Like a magic potion, a recipe is a spell that conjures up the past and evokes associations with others across geographical and temporal distances. A beloved recipe is also a love letter, for it expresses a longing, a hunger that speaks to a deep emptiness in our bellies, but perhaps also in our hearts for those who have gone without return.

The first eight dishes on Jayanto’s menu for the ritual gathering at the Art Atrium Gallery are those traditionally prepared for his family’s Lunar New Year celebration. This is no coincidence because the number eight is traditionally the luckiest of all numbers and symbolises wealth and success. The first dish on the menu is Siu Mie, also known as longevity noodles, which symbolise the desire for long life, with the noodles left uncut during cooking and eating so as not to shorten life. In the spirit of sharing and connection, and to invoke the spirit of potluck from afar, I asked Jayanto if he would like to share a recipe with me, and he responded with a story about his Siu Mi.

Born and raised in a small village of 500 people in North Sumatra, Indonesia, seven hours from Medan, the family’s typical diet consisted of farm chickens, vegetables and lots of eggs. Jayanto recalls, “Our village is not even on google maps. There were no luxury ingredients, you ate what you had. My sister would go to town once a month to buy Chinese products like soy sauce, fish sauce, and so on.”

So, what seems to me to be a simple list of ingredients is a dish rich in cultural and relational complexity. The dish is a tribute to Jayanto’s Chinese father from Guangdong, who, like the so-called ‘real’ Chinese, preferred wheat noodles – unlike Jayanto’s Indonesian-born Hokkien (Peranakan) mother, who preferred rice. His father died when Jayanto was only five years old, so he remembers him only indirectly through oral stories and offerings of food from his mother, sisters and aunts. This was coupled with the socio-political difficulties of being the only Chinese family in this remote town during the authoritarian term of Indonesian President Suharto, when Chinese Indonesians were actively discriminated against.

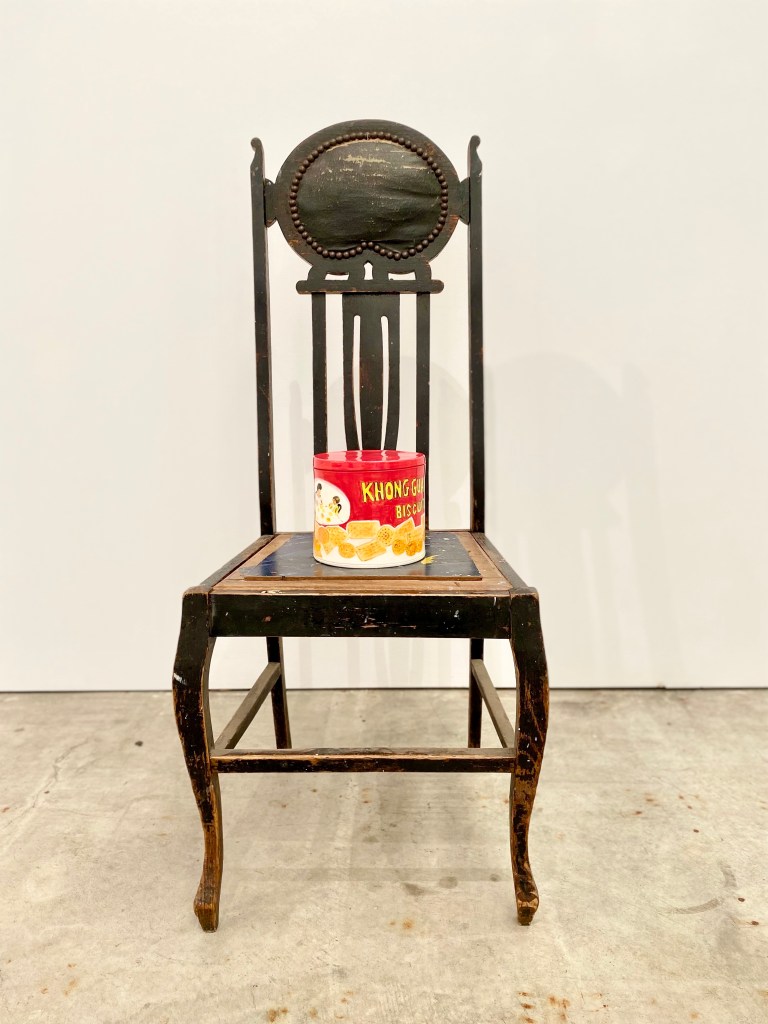

At its core, the Ritual Gathering Potluck Party is about a very personal reliving of childhood memories, creating a new home in Australia and dealing with cultural differences. To research his ceramic desserts, Jayanto attended an “Australian Sweets” cooking course at TAFE. The result is a joyful abundance of vibrant ceramic delights, including not only delicious Century Eggs, Hainanese Chicken Rice, Waterfalls in the Moon Garden, but also Kiwi Mango Coconut Pavlova as well as Mini Colourful Lamingtons, to name but a few.

The effect is one of enticement and invitation, not unlike the hyper-realistic plastic replicas of food you see in the windows of some Japanese and Singaporean restaurants. “Sampuru” is the Japanese term for the art of food fakery or sampling, originally made from wax almost a century ago. Today, these lifelike but inedible replicas of food made of plastic or resin never go bad, ferment, mould or melt, so they capture a fleeting moment. Jayanto’s ceramic foods also entice with their liveliness, but cannot be eaten either and thus represent an insatiable longing, a phantom meal. This insatiable craving is reminiscent of the Chinese festival of the Hungry Ghosts, when forgotten ancestors return to the world of the living with swollen bellies and long, thin necks in search of sustenance. Hell money, also called Joss paper, only imitates legal tender, but is nevertheless burned to transfer its value to the dead in the afterlife. Similarly, Jayanto’s ceramics are offered to us as replicas of the “real”, and as they are fired, the clay undergoes its own transformation. These rituals are informed by the belief that the dead, even when they are absent and can no longer express themselves, still have the power to influence the living.

This doubling of “authenticity” and “imitation” runs like a thread through Jayanto’s work, which he describes with both humour and seriousness as follows: “It’s not really double happiness, it’s a double dislocation from A to B, double suffering. I can never be myself at the moment, I’m always adapting to people, to the majority of people.” Jayanto’s colourful ceramics radiate positivity, but there is also a turbulent history of negativity behind them. Like an apparition or a rainbow, the work is a homage to indeterminate identities that are there for a moment and then disappear. Jayanto’s work is a conversation with ghosts and also with a living community of people who are othered and honours what is not fully known between us.

A hungry ghost is an apt metaphor for people living in culturally marginal spaces far from home, “home” being an elusive term. This is not about a sentimental longing for a place to which we can never return, but about a very specific and unsettling pain. Here in Berlin, my craving for the taste of wild coconut pandan sago and spicy sambal is a constant reminder of where I am not and what is not readily available here. These tastes don’t usually belong here, so I can only adapt or get creative and develop my own magical spell recipes. So, with Jayanto’s list of ingredients in hand, I went to the only known Indonesian supermarket in Berlin and discovered that it is not only a small grocery shop, but also a meeting place for the Indonesian migrant community. In searching for Jayanto’s secret recipe and trying to recreate his replica, I was reminded that it is impossible to reproduce a memory, that the exact ingredients can never be duplicated, yet another transformation takes place that can bring us closer together, and that this is also why we treasure the experience of fleeting encounters.

But enough of these words, let us now raise our glasses to celebrate with Jayanto and wish us all a jolly meal, memories and imaginations of a new future.

It was so lovely to attend Jayanto’s Ceramics/Sweet Treats workshop. We had so much fun and learnt a lot.

I really love Jayanto’s art style-showing the beautiful Peranakan culture to the world! What a wonderful heritage we have!

We look forward to attending more of Jayanto’s workshops in the future and learning more about ceramics.

May God give you many blessings, Amen 🙏

LikeLike