The ‘Ritual Ceng Beng’ exhibition responds to a photograph taken in the 1970s, capturing the traditional Chinese Ceng Beng ritual performed by a family at a cemetery in North Sumatra, Indonesia. The exhibition incorporates food, performance, and mixed media installation with reference to ideas of identity, migration, and cross-cultural histories.

Curated by Kyle Weise

Essay by Dr. Siobhan Campbell

Photograph by Kyle Weise and Jayanto Tan

This exhibition has been conceived around a photograph taken in the mid-1970s which depicts the scene of a family ritual in a cemetery in a rural part of North Sumatra, Indonesia. The artist appears here as a young boy, alongside his mother, brothers, sisters and brothers-in-law standing to either side of a tombstone. In front of them an array of edible offerings has been placed on the ground, including plates stacked with a variety of steamed cakes, fruit and noodles. To the right a green box is visible, a treasure chest filled with paper versions of clothing, money and other worldly goods, which will shortly be burnt on the ground behind the tombstone. The rented jeep they have travelled in is visible in the background, parked a short distance from where the family has gathered.

Ceng Beng (in Hokkien or Qing Ming in romanised Mandarin Chinese) is performed during the second or third lunar month of the Chinese calendar to remember of one’s ancestors. It involves the cleaning and sweeping of graves and offering food and prayers to the deceased. While the atmosphere captured in this image appears to be that of a jovial family gathering, this intimate record of a family performing the Ceng Beng ceremony took place at a time when expressions of Chinese identity were taboo. President Suharto, who seized power in 1965, had supressed public displays of Chinese language, religion and culture and closed Chinese schools and organisations throughout Indonesia. While the practice of Ceng Beng was not prohibited outright, in a landscape where Indonesia’s ethnic Chinese endured systemic discrimination, this photograph documents a family in a small act of resistance to the nations.

Much of Jayanto’s work examines a sense of belonging, of belonging to families and belonging to nations, which draws on his life experiences beginning in a small village near the town of Bandar Tinggi in North Sumatra. Both his parents were of Chinese descent, but his mother’s family was peranakan Chinese, meaning that they had lived in Indonesia for four or five generations and had intermarried with the local population, while his father had migrated to Sumatra with his parents as an adolescent. Jayanto’s mother could speak Hokkien, but the language of the household was a dialect mixed with Malay. When Jayanto lost his father at five years of age, several of his older siblings had already married, and his mother continued to tend to a small landholding at the back of their house, growing cassava, pineapples and bananas to sell. He attended the local primary school where there were a few other ethnic Chinese students, and some Javanese immigrant students, but mostly Batak and Malay. When he was 17 years old, Jayanto’s mother, with almost all his eight siblings, decided to move the family to the capital, Jakarta, in search of better livelihoods. Jayanto spent several years studying accounting in Jakarta before moving between Yogykakarta and Bali. In 1997 he migrated permanently to Australia.

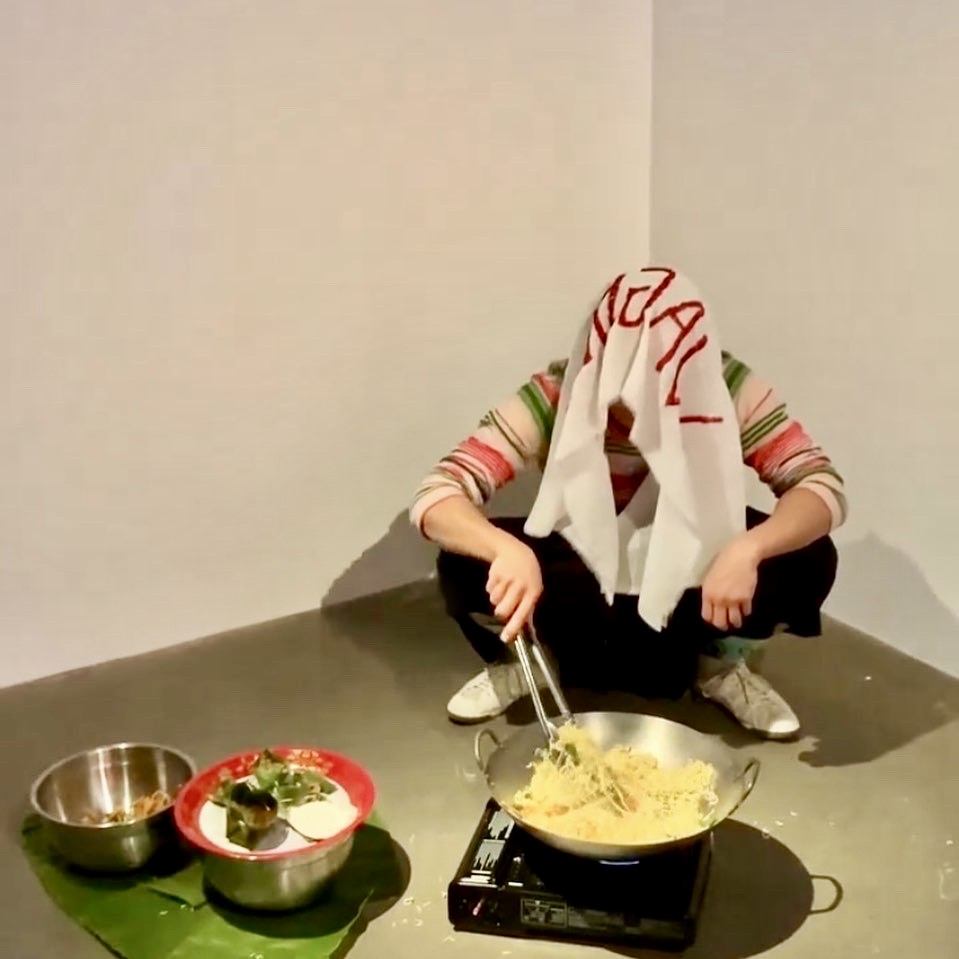

The Ceng Beng ritual reenacted in the gallery space draws on the memory of his family not long after the death of his father. As Jayanto recalls, he didn’t like performing Ceng Beng as a young child because he was acutely aware that this was a display of cultural difference. On the occasion captured in the photograph, the ritual was quite elaborate. There are the red oval-shaped rice flour cakes (kue angku) with a sweet filling of mung-bean paste in the centre, the pink steamed cupcakes (kue mangkok) and the sweet buns (bak pao), which Jayanto frequently recreates in ceramic form. However, it wasn’t always necessary to visit the gravesite as the rites could be performed at home, and the offerings could be quite simple. Though, Jayanto remembers, noodles were always part of it.

The noodles Jayanto has produced here refer to the ubiquitous instant noodle brand Indomie, first launched in Indonesia in the early 1970s and soon after being sold with the flavouring to create mie goreng (fried noodles), a popular dish believed to have been introduced by Chinese immigrants. The noodle dishes that Jayanto’s peranakan mother prepared for him as a child were made using locally produced fresh noodles, but by the time the family migrated to Jakarta in the mid-1980s instant noodles had become a cheap and convenient way of preparing food in lodgings which lacked a proper kitchen. The family rarely ate together in Jakarta as they were all out of the house working, returning home only to sleep. In this context, and as for many working-class Indonesians, instant noodles came to be a mainstay of their diets. Throughout Indonesia, the banana leaf is commonly used as a disposable plate and to wrap and cook different foods. In using both instant noodles and banana leaves as part of his performance, Jayanto intentionally dislodges notions of cultural authenticity by bringing the instant noodle into the realm of the family ‘tradition’.

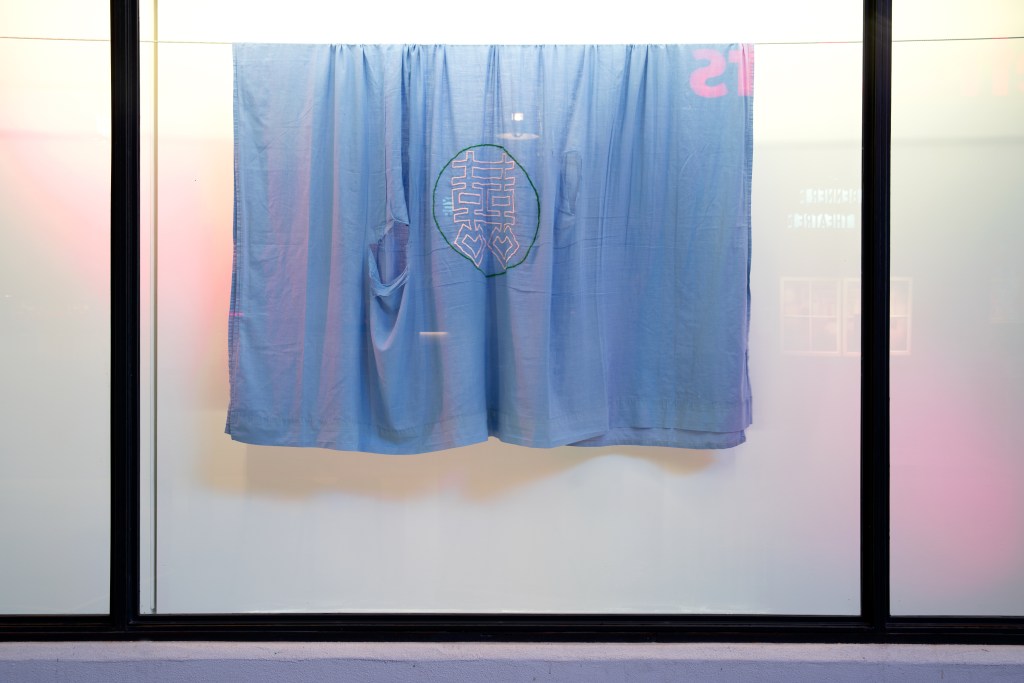

In the same manner of intentionally re-enacting a tradition as a form of defiance, Jayanto has created a backdrop for this scene of fabric panels featuring the Chinese ornament design ‘double-happiness’ (shuāngxǐ). This is a commonly used as a decorative motif in Indonesian Chinese wedding ceremonies, often written in red or gold and pasted on walls. Here it stands for the struggle for marriage equality in Australia, and in Indonesia, where same-sex marriage has not been recognised. Just as Chinese culture was once considered a threat to Indonesian moral values and culture under the regime of former President Suharto, Indonesian opposition to homosexuality is often based on the notion that it is incompatible with Indonesian culture. Jayanto likens the cloth panels to the screens used in the traditional layar tancap, open air film screenings, once a popular way to experience the cinema. And with this Jayanto invites the viewing audience to share the intimate realm of personal memories and narratives that define his practice.